Hey you, the house ghosts overstayed and now I can’t get them out of the bedsheets. They snuck into the gap between the double glazing and I can’t suck them out, they’re upright, sticky, filtering the daylight with their bumper-sticker quips. We’ve been living inside so long and now the world has 4 walls. 4 walls anthropomorphic. I can see our breathing getting under its skin and producing poisonous spores that will get into our breathing and poison us. I see in reds and greens and the worst in everything (e.g. how to spot a blood clot). A lockdown diary entry from a year ago goes: O! This was meant to be an ode-less day, I will be joyful later now that I have made a note to do so.

What is poetry? A clown laughs, a clown weeps, dropping his mask.

Poetry is the Unknown Guest in the house.

That’s Lawrence Ferlinghetti from Poetry As Insurgent Art. Let’s get down to the warm mechanics: home unmade for visitors, home at its most utilitarian. The poem is what’s behind the mask, the poem is really an intruder, an intrusion, the uncanny lurking, making remarks, finding our mundane strange or vice versa. Eyeing up the valuables, licking the stew spoon. Can we get down-to-earth if we’re stuck inside? The idea of surveying our sty prompts the kind of morbid exhilaration as looking in the mirror after a big night out. What is the ecology of this house? Is it rich and delicate as a forest? Could it be as vast and complex as another world? First, I’m a cynic, like Barbara Guest in her poem Green Revolutions,

Being drunk upstairs and listening / to voices downstairs. … Distant greens … landscape appears / with its fresh basket, approaching the car / then relinquishing, going away, telling us / something that is secret, not even whispering … I’m upstairs “looking at a picture” / like a Bostonian in Florence, “looking at a picture.” / Now it’s green. Now it isn’t.

Oh, the pretensions that remain unruffled in these private places, that affectation of the inner voice. Let’s let them loose against the agents that tell us secrets and don’t even bother to whisper, for whom there is no threat of etiquette. What fresh basket, what secrets. “Looking at a picture” like looking at Earth from Sirius. Let’s get among the brushstrokes, those motions. What seems miraculous might be as tangled and troublesome as a crime-scene. Poet Zefyr Lisowski is inspired by probable axe-murderer Lizzie Borden. From POEM IN WHICH NOTHING HAPPENS, AUGUST 3RD, 1892:

I never write about my sister Emma, who is never at ease in this maze, I mean house, I mean spite. She says, we have walls to keep secrets, and locks to hold them tight.

…

I will be 32, which also is a type of box. I walk the thin floors of my bedroom every day, hearing the bicker and creak of the house. The only relief we have is supper—another geometry, another violence too.

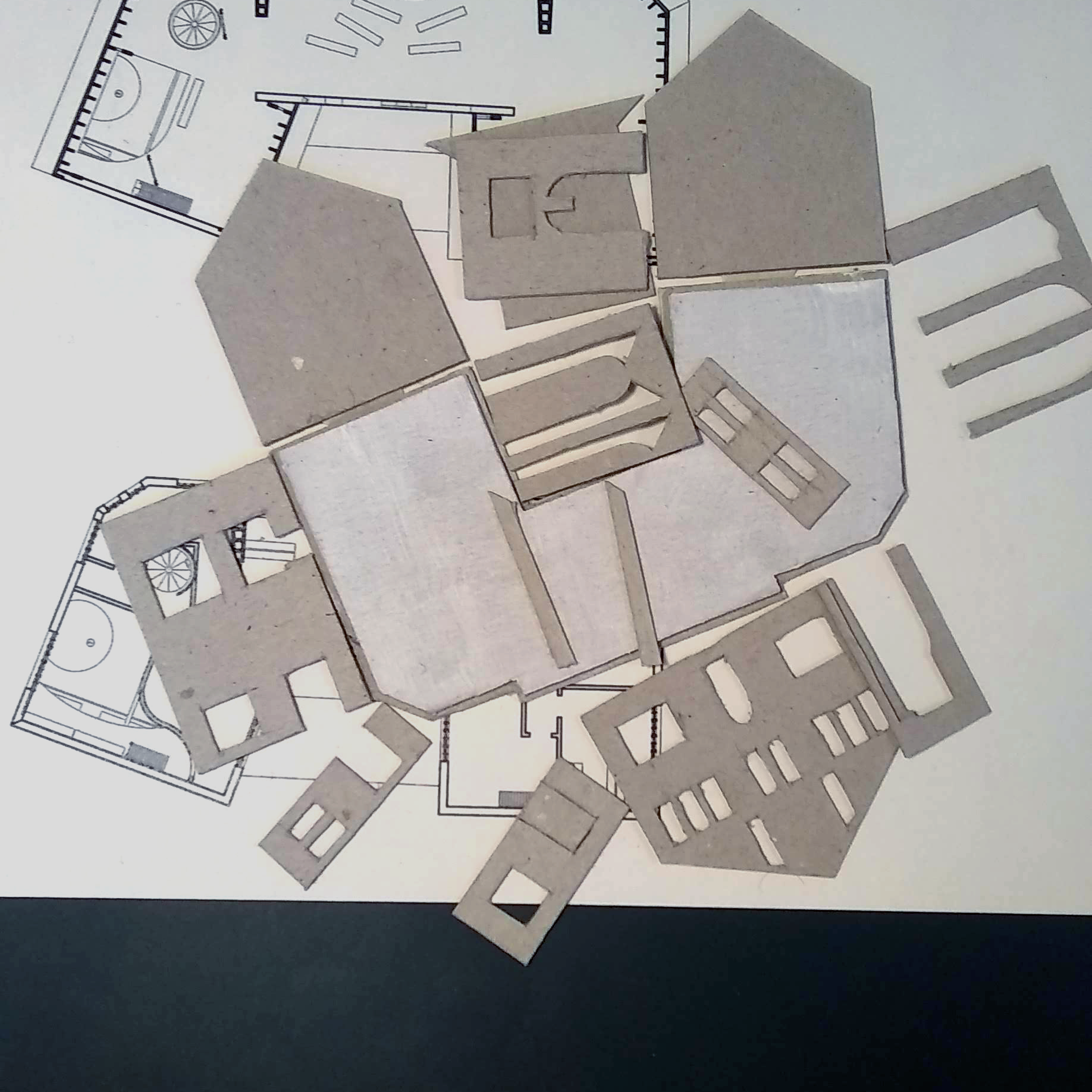

To be embedded can be unpleasant, and sometimes unsafe. What we know we need might remain out of reach. We can at least discover in this network what responds with protection, and what with challenge. Living amongst, walls and locks can serve to keep vulnerabilities safe from incursion. But these devices aren’t unresponsive, they bicker and creak, and make this work heard. Sometimes the fraught vectors of interconnection are clearly legible, like lit-up laser beams in heist movies, supper—another geometry, another violence too. These maps are drawn in the negative of need but, like light falling around obstacle onto the paper, we hope they will eventually reveal a way out of the shadows.

The other day I walked slowly in flat sunshine metres behind an old man who turned out to be the bloke who sells Manuka honey and menstrual cups. He’s very pale, like a faded billboard running out and regressing to what was before. It’s like he’s onstage but he kept getting distracted by some detail in the forest, eddying off into spikes but being gentle, hardly touching, he seemed to be recording edges and creases and lips, spray, run-off, indigestible pellets. The park was like a neglected wallet got fat and he was taking out all the receipts, one by one ironing them between his palms into a neat pile before putting them back.

That is what he was doing to the park, when he arrives he is taking the park out of his pocket and opening it up.

Is it easy (too easy) to think of one geometry as foundational, and the others auxiliary? The geometry of supper imposed [superimposed] onto a controlled floorplan, awaiting the critical outburst when one can no longer contain the other. Behind the floorplan, another geometry governs and determines the feasibility of escape, it is loud in our minds and in the calibre of our household props. Lisowski writes in Girl Work:

I pay my rent and go to the rent store

I buy a new shiny rent

I buy a tight fitting outfit to tell myself I am rent

The weather shiny

The sun flecked with little bits of wealth

Hello I am looking for feedback and also rent

Between 4 walls, sqm valuation determines arable land. This world’s self-critic is economic. Even the last vestiges of common goods, air, sun, conversation, are written as luxury commodities in the assured narration of somebody either out-of-this-world or masquerading glam in the face of barely getting by. In Girl Rent the landlord is antagonist and absentee; this poem’s thinking has gotten world-big and has no use for smalltime villains. Also the reverse, the world-big rent has shrunk to fit into our sense of self. This is the view from the window. We read risk in all our terrestrial investments. In Bunny by Sophie Collins, a hostile letting agent responds to complaints about dust. This is the world in our inbox. They deem us a risky investment.

You need to forget about the dust.

…

Do you want to lose your children? I met them earlier

in the foyer, if you remember, and they didn’t

cough once. Don’t blame the dust for your poor parenting;

the dust is not an autonomous entity. The dust appears

if anything, to be synonymous with your own

sense of guilt, and if that’s true, then all is dust, these words, Bunny.

Why didn’t you act sooner? Why don’t you show me a sample. It’s not flecked with wealth, but a danger to our health. Or not. It’s fabricated, it’s psychosomatic, it’s guilt, which means it’s a pain in the ass and steer clear. We’ve been living between 4 walls intensely for over a year and I’m easily persuaded by this accusation, all the muck rises to the top, and it looks a lot like something my skin sheds.

Maybe through the pandemic we’ve been getting better at verbalising how we care, we can’t rely on facial expressions or subtext any longer. Maybe we have a better sense of how we’re embedded and which beings we actually need. Maybe we’re just breathing guilt or dead skin cells. But here, I think the dust and the rent are conditions, not beings. They possess no forces of gravity or magnetism, they’re endured, they don’t endure. At some point we should call them out as self-interested and extract ourselves from their network. They can’t care: that’s our superpower. We should be superterrestrials, but don’t let it go to your head. Your care isn’t yours if it’s real. It flows towards what you care about. Thank god, the world isn’t made of the map, but sometimes I need reminding. All this drawing, drawing as a way of thinking about what I need. Drawing you out of your dwelling spaces. The motion that surrounds the focus.

You are the one

Solid the spaces lean on, envious.

You are the baby in the barn.

Thanks Sylvia.

Mentioned and recommended:

– Who Is Mary Sue? by Sophie Collins (poetry collection)

– Poetry as Insurgent Art by Lawrence Ferlinghetti (poetry collection)

– Blood Box by Zefyr Lisowski (poetry collection)

– The Collected Poems of Barbara Guest